On Friday I went to visit my friend Alta Gracias and her three children at Karnes County Residential Center, where they have been locked up for the past two months. I was accompanied by a volunteer from the Hutto Visitation Program, a community group in Texas that has visited detained immigrants since 2009. We drove about three hours into Southern Texas, past oil derricks, cotton fields, and small, economically depressed towns. The Karnes facility, originally constructed as a model center for the detention of adult migrants, was repurposed this summer and began detaining families last month.

Aerial view of Karnes Detention Center

Upon arrival, I turned in my ID and was given a visitors badge. At the direction of the guards, I proceeded through a metal detector and two locked doors into the visitation room, taking nothing with me except quarters for the vending machine. The two older children, 10-year-old Ana and 9-year-old Victor (not their real names) were bouncing with excitement to see me. As soon as the door to the visitation room locked behind me, four small arms wrapped around me and two heads burrowed into my sides. When they finally let go, Alta Gracias’ hug felt no less desperate. As we sat down at a table to visit, Ana snuggled up close to me, my arm around her shoulders, until the visitation guard told me that the little girl needed to sit on her own chair. The desperation of the children’s need for comfort spoke volumes about the depth of their suffering during their dangerous journey north, in the week they spent sleeping on the floor in crowded and freezing holding cells at the border, and during two months of waiting, trapped at the detention center.

Alta Gracias and her children are being held for crossing the border without documentation, fleeing extreme violence in the coastal part of El Salvador they call home. While children who cross the border alone are quickly released to relatives or sponsors while they go through immigration hearings, children who come with their parents are locked up in family detention centers like Karnes, which holds 550 mothers with children as young as two months old. They are held in these facilities while they go through the slow legal process of determining whether they have a possible asylum case or not. Those who manage to convince judges of the viability of their asylum claims may then have the opportunity to negotiate bonds under which they can be released from detention while awaiting further hearings.

Alta Gracias told me that, in her case, immigration officials had told her this process could take up to six months. That means four more months of incarceration, of institutional life, of heavily processed food, of sharing a living space (four bunk beds, one shower, and one toilet) with two other families. With fierce determination on her face, Alta Gracias told me that this was a sacrifice she was willing to make for the wellbeing of her children, for a future free of the constant threat of violence. Her children are already suffering the consequences of their incarceration: 10-year-old Ana has angry outbursts or fits of sobbing almost every day, 9-year-old Victor has become sullen and withdrawn, and 2-year-old Martín takes out his frustration by hitting other children. All of them have lost weight.

The experiences of Alta Gracias and her children are not unique. In a recent statement, the ACLU summarized research and reports on past family detention: “History shows us that imprisoning families limits access to due process, harms the physical and mental health of parents and children, and undermines family structure by stripping parents of their authority.” The United Nations is also opposed to the incarceration of children, stating: “detention of children on the sole basis of their migration status or that of their parents is a violation of children’s rights, is never in their best interests and is not justifiable”.

How is the continued incarceration of these children justified? The Department of Homeland Security, which is responsible for immigration oversight, has argued that these women and children must be detained because they constitute an indirect national security threat. They seem to have decided that the solution to increasing migration from Central America is to lock up women and children, attempting to turn their suffering into a deterrent of further migration, rather than taking a serious look at the root causes of this exodus and our role in creating the situation in the first place. So families like Alta Gracias and her children pay the price for a history of U.S. involvement in Central America that has prioritized economics and politics over people.

The incarceration of these families is yet another policy that puts economic gain first. The detention centers where these women and children are locked up are all run by private corporations like Geo Group and Corrections Corporation of America (CCA). For these corporations, which have recently been averaging $5 billion in annual profit from immigrant detention, the increase of refugees from Central America presents a new source of revenue. Through their powerful Washington lobbies, which in 2005 spent more than Goldman Sachs and Wells Fargo combined, these corporations have sold for-profit detention as the solution to the border crisis.

The incarceration of these families is yet another policy that puts economic gain first. The detention centers where these women and children are locked up are all run by private corporations like Geo Group and Corrections Corporation of America (CCA). For these corporations, which have recently been averaging $5 billion in annual profit from immigrant detention, the increase of refugees from Central America presents a new source of revenue. Through their powerful Washington lobbies, which in 2005 spent more than Goldman Sachs and Wells Fargo combined, these corporations have sold for-profit detention as the solution to the border crisis.

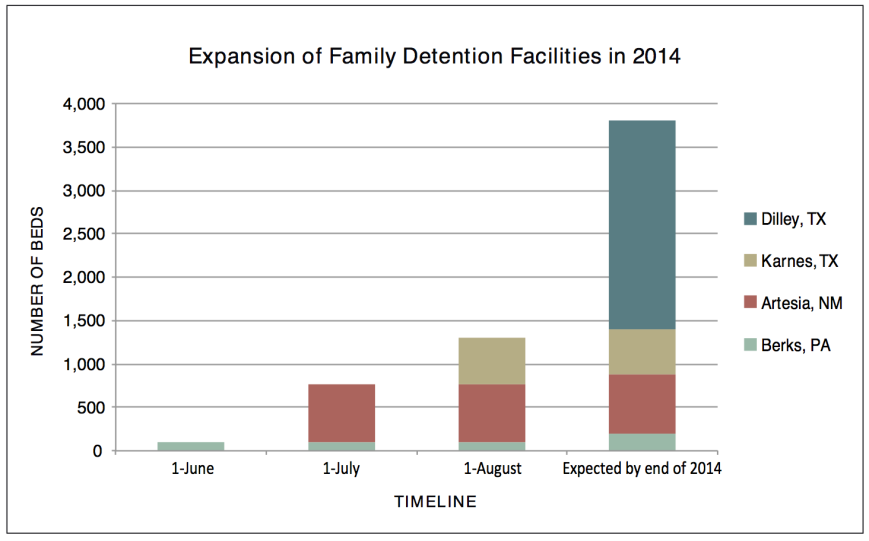

As a result of this lobbying, for-profit incarceration of immigrant women and children is increasing sharply. Just this week, the Department of Homeland Security announced plans to open a new center in the remote town of Dilley in South Texas. The facility, which will be operated by CCA, is planned to open in November and will have beds for 2,400 women and children, making it the largest immigrant detention facility in the nation. In addition to the new detention facilities in Karnes, TX and Artesia, NM, this plan increases family detention from 90 beds to almost 4,000 beds since June of this year. This rapid expansion means that many more families like Alta Gracias and her children will be incarcerated, in the largest trend of family detention since the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

As a result of this lobbying, for-profit incarceration of immigrant women and children is increasing sharply. Just this week, the Department of Homeland Security announced plans to open a new center in the remote town of Dilley in South Texas. The facility, which will be operated by CCA, is planned to open in November and will have beds for 2,400 women and children, making it the largest immigrant detention facility in the nation. In addition to the new detention facilities in Karnes, TX and Artesia, NM, this plan increases family detention from 90 beds to almost 4,000 beds since June of this year. This rapid expansion means that many more families like Alta Gracias and her children will be incarcerated, in the largest trend of family detention since the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

At the end of our visit, Ana wanted to know when I would be coming to visit them again. Alta Gracias told me that, before my visit, the little girl had thought I would be staying with them for several days, as I always did when I visited them in El Salvador. Ana had been worried that there wasn’t enough space for me in their crowded living quarters. For my part, I had been worried that the children would ask me to take them with me when I left, to get them out of detention. But they didn’t, and in some ways that silence was even more devastating because it suggested that they children had started to think of prison as the normal place for them to be. As I walked free at the end of the day, leaving Alta Gracias and her children behind, I was weighed down by the knowledge that legacies of trauma sprung from imprisonment would continue lay claim to ever more children until the practice of family detention is ended.

Many people have asked me how they can help, what they can do for Alta Gracias and her children and all the other families who are being detained. Here are some suggestions:

- Educate yourself. Far too few Americans are aware of how our government is using detention to respond to the “border surge”. Two excellent short documentaries are Immigrants for Sale, about for-profit private detention, and America’s Family Prison, which includes testimonies of women and children who have been locked up. For children and teachers, a new educational website “When we were young, there was a war” gives some historical background to today’s situation in Central America.

- Speak out. There are petitions currently online here and here demanding that family detention be stopped. The private detention industry has a lot of money behind it, so politicians really need to be held accountable to the morality of their decisions.

- Donate. There are many groups around the country, but especially in Texas, that are working to help detained immigrants. You can donate to Grassroots Leadership to support those who visit detained women immigrants with the Hutto Visitation Program, as well as their advocacy efforts through Texans United for Families. To support alternatives to detention, consider supporting Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services, which has opened Houses of Welcome to provide shelter and care for immigrant families as they go through their immigration processes.

- Visit detained immigrants. A non-profit called CIVIC has a nation-wide network of 33 community-led programs that visit immigrants in 17 states. Even if you don’t think you live near a detention facility, check out this interactive map of immigrant detention facilities around the country. You might be surprised.

- Spread the word. Help others to learn more about the difficult situation faced by these Central American families and children. Here in Santa Barbara, I have helped organize a humanitarian vigil, which we hold every two weeks, to continue calling attention to their plight. The Humanity is Borderless Campaign has many good resources for starting an effort like this in your own town.

Pingback: Imprisoning Families for Profit | CIVIC: Blog

Pingback: Help Reunite a Family | Alas Migratorias

Pingback: Let my people go! | Alas Migratorias

Pingback: Fasting For Freedom | Alas Migratorias

Pingback: Shut it Down! Set them Free! | Alas Migratorias

Pingback: Help Reunite a Family | End Family Detention